The text of this short biography is adapted from a pamphlet printed for Grolier Club members soon after the founding of the Club. The circumstances of its publication are obscure, but there is evidence to suggest that it was the very first publication of the fledgling Grolier Club. It was issued without title-page or imprint, and the text is signed at end simply with the initials "C. A." On the fly-leaf of the Grolier Club copy is the inscription: "Written for the Grolier Club by Charlotte Adams, 1884"—Editor.

IN THE HISTORY OF BOOKMAKING, no more interesting and brilliant figure is to be found than that of Jean Grolier de Servières, vicomte d'Aguisy. Treasurer-General of France, ambassador to the Court of Rome, and bibliophile, his life forms a complete, epitomized expression of the higher literary feeling of his time. Grolier was born at Lyons in 1489 or 1490.(1) His family was of Italian descent, originally from Verona; his father, Étienne Grolier, a gentleman of the Court of Louis XII of France, and Treasurer to the King in the Duchy of Milan. At an early age, Grolier was introduced at the French Court by his father, where he soon attracted notice, both by his learning and by his talents as a financier. Under François I he held the position of intendant of the army in the Milanese country. He returned to France after the battle of Pavia, and was appointed ambassador to Pope Clement VII in 1534. In this capacity he conducted certain diplomatic negotiations with so much delicacy and skill that he won the personal friendship of the Pontiff, who gave him substantial proof of his favor.

During his stay at Rome, Grolier began collecting a library. Upon his return to France he was first appointed Treasurer of the King for the districts of Outre-Seine, and L'Ile-de-France, and afterward Treasurer-General of Finance, an office which he held until his death, displaying ability and integrity in his administration of the public money, and, notwithstanding the malicious accusations which were brought against him, completely triumphing over his enemies. He died at Paris on the 22nd of October, 1565, at the age of about seventy-five years, and was buried in the Church of St. Germain des Prés, near the great altar.

The interest attached to the name of Jean Grolier in the mind of posterity has far less to do with his distinction and personal merits as a financier than with his passion for books. He loved books as a man of letters, as an artist, and as a dilettante. Both at Paris and in Italy, he had many warm friends among the learned men and the men of letters of his time, to whom he accorded a generous and delicate protection. He was linked also by ties of common interest and sympathy of pursuits with the most famous printers of the epoch. Garuffi, Étienne Niger and Budé dedicated books to him. It was Grolier who caused Budé's treatise De Asse to be printed by the Aldines in 1552. An example on vellum of this volume, that which was presented to Grolier and brought 1500 francs in 1816 at the MacCarthy sale, afterwards found its way to England. Dedications to Grolier are also seen at the beginning of a Suetonius printed at Lyons in 1518, of a book by Étienne Niger on Greek literature (Milan, 1517), and of different other works. In many writings of the time, Grolier is spoken of in terms of the highest commendation. Erasmus bestowed great praise upon him. Coelius Rhodigimus, Aldus Manutius, Baptiste Egnazio, and various other persons dedicated works to him. It is Egnazio who related that Grolier, having invited several learned men to dinner, at the close of the repast set before the guests gloves, in each of which was wrapped a considerable sum in gold.

The historian De Thou compares the famous library of Grolier with that of Asinius Pollio, the most ancient library of Rome. Only such books were included in it as were remarkable for their intrinsic literary value and their beauty of form. The Greek and Latin classics, the works of contemporary philosophers and learned men, historians, geographers, archaeologists, composed a great part of it. By the side of these figured the modern Latin poets, which were read at that time, and the literature of Italy. For this library Grolier selected the best copies procurable of the different works, and frequently caused several copies of a book to be printed especially for him on fine paper. He had the frontispieces and the initials painted in gold, and in colors. The covers bore ornaments in the most exquisite taste, and were gilded with remarkable delicacy. The compartments were painted with various colors, were perfectly well-drawn, and all were designed in different figures. Grolier even went so far as to have new margins carefully added to the leaves which had been left too short in the folding, in order to possess copies with very wide margins. But it is particularly in the bindings which he caused to be made, that Grolier gave the most positive proofs of his admirable good taste. The art with which they were executed was no less remarkable than the beauty of the ornaments which he himself designed.

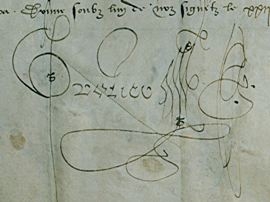

Most of the books of Grolier's library bore on one side his personal motto, Portio mea, Domine, sit in terra viventium [Lord, let my portion be in the land of the living—paraphrase Psalm 141, v. 6], and on the other the words, Io. Grolierii et amicorum [of or belonging to Jean Grolier and his friends]. This latter inscription has given rise to the theory that Grolier was a bibliophile of an uncommonly generous disposition, and regarded his books as the property of his friends as well as of himself. Another theory, upheld by authenticated facts, is that Grolier, possessing several copies of the same book, all richly bound, was in the habit of reserving the finest copy for himself and distributing the others among his friends.

The famous library remained intact for a century, and was not scattered until 1675. The cabinet of medals belonging to the Treasurer-General was at the same time about to be transported to Italy, but Louis XIV caused it to be purchased at a high price, being unwilling that the French nation should lose so valuable a collection. To-day the richest public libraries account it an honor to possess books bound by Grolier; bibliophiles seek for them with an eagerness which is constantly on the increase, as is abundantly proved by the high prices certain of these volumes have brought in recent years at the public sales in Paris. In 1854 the Adages of Erasmus (Aldus, 1520, in folio) were sold for 1,729 francs; the Virgil of 1527 (Aldus in 8vo.), at 1,600 francs; the treatise of Marsile Ficin De Sole (1490 in fol.) brought 1,500 francs; the Letters of Pliny (Aldus, 1508, in 8vo.), 1,106 francs. In March, 1856, at the Hebbelinck sale, the Catullus of Aldus, 1515, brought the then enormous price of 2,500 francs. The Cicero of the Giunti, 1536 to 1537, five volumes in folio, violet antique morocco, sold for 1,485 francs at Decotte's in 1804, but was sold again for only 902 francs at Didot's, in 1810. A volume purchased for 1,600 francs in 1853 was sold for 1,905 francs in 1860, and 2,850 in 1863. A simple octavo volume has been sold at the price of 3,750 francs. Many other single volumes have brought from 400 to 800 francs.

Among different amateurs who undertook to make collections of volumes bound by Grolier, may be mentioned, Renouard, the learned historian of the Aldus Manutius, and of the Estienne families, and Coste, a magistrate of Lyons. Their collections have been scattered; but that of another citizen of Lyons, M. Yemeniz, and that formed by Lord Spencer, still exist and contain very valuable examples. The Bibliothèque Nationale, in Paris, and the British Museum in London, possess fine specimens of the Grolier library. The legacy to the museum of the collection of Sir Thomas Grenville brought six of these precious volumes within its walls. There are books from Grolier's library in the Columbia College and Astor libraries; also several in private collections in New York.(2)

Jean Grolier de Servières may be regarded as one of the typical figures of the French and Italian renaissance. He belonged to both countries by ancestry, by residence, by achievement, by love and protection of art and letters. Fate made him a Frenchman, but he drew his inspiration from Italy and the Italy of the cinquecento. He had more in common with the great nobles of Florence, Venice and the Verona of his ancestors, than with the courtiers of the French capital. His influence on the French revival of art and literature was incalculable. His travels and residence in Italy and the knowledge of men, of books, of art and of places acquired in that country made his judgment in such matters valuable to the king, Henri II, whose name is identified with the renaissance in France. Grolier formed an important link between France and Italy in art and letters, as well as in diplomacy, finance and arms. The character of the Treasurer-General of France offers a singular mingling of the positive and the ideal. A little more of the positive element in his composition, and his love of art and letters would have been entirely lost in political ambitions and the cares of state. A slight preponderance of the ideal element would have made of him a man of letters and a poet, perhaps a painter or a sculptor, for the age of art frenzy in which Grolier lived set nobles and peasants side by side in the passion of artistic creation. Being what he was, an evenly balanced, symmetrical individuality, Grolier has left his mark on history as a brilliant, successful man of the world, of broad and generous sympathies, whose business in life was finance and diplomacy, whose recreation was art and letters. He was equally at home in palace, camp, council chamber, treasury, studio and printing room. His list of friends and acquaintances began with kings and popes and ended with artisans and toilers among the people.

Jean Grolier de Servières may be regarded as one of the typical figures of the French and Italian renaissance. He belonged to both countries by ancestry, by residence, by achievement, by love and protection of art and letters. Fate made him a Frenchman, but he drew his inspiration from Italy and the Italy of the cinquecento. He had more in common with the great nobles of Florence, Venice and the Verona of his ancestors, than with the courtiers of the French capital. His influence on the French revival of art and literature was incalculable. His travels and residence in Italy and the knowledge of men, of books, of art and of places acquired in that country made his judgment in such matters valuable to the king, Henri II, whose name is identified with the renaissance in France. Grolier formed an important link between France and Italy in art and letters, as well as in diplomacy, finance and arms. The character of the Treasurer-General of France offers a singular mingling of the positive and the ideal. A little more of the positive element in his composition, and his love of art and letters would have been entirely lost in political ambitions and the cares of state. A slight preponderance of the ideal element would have made of him a man of letters and a poet, perhaps a painter or a sculptor, for the age of art frenzy in which Grolier lived set nobles and peasants side by side in the passion of artistic creation. Being what he was, an evenly balanced, symmetrical individuality, Grolier has left his mark on history as a brilliant, successful man of the world, of broad and generous sympathies, whose business in life was finance and diplomacy, whose recreation was art and letters. He was equally at home in palace, camp, council chamber, treasury, studio and printing room. His list of friends and acquaintances began with kings and popes and ended with artisans and toilers among the people.

The external conditions of his life were such as only the sixteenth century could show, but its inner mainsprings of action were of no country and no age. Stripping off the brilliant outer garment of his many-sided life, the nineteenth century might claim lawfully Jean Grolier as the representative of its own mingling of complex forces and interests. The type presented by the figure of Grolier, of successful, practical manhood, using the fruits of its serious labors to adorn its leisure hours with the charms of art and literature, is one essentially contemporary and modern. Grolier's cosmopolitanism, too, was that of the nineteenth century.

The fruition of this noble existence, compounded of so many varied and significant elements, is to be found in the results attained by Grolier in his efforts to give a worthy, tangible form to human thought and its literary expression. He loved books, not only for what they contained, but what they were. In clothing the masterpieces of literature in sumptuous garments, the impulses of art and literature within him, which were not strong enough for original creation, found an eloquent utterance.

Grolier was a princely protector of men of letters, but still more was he a protector of the men who gave to literature its enduring form. He was a patron of art, but it was art as contributing to the glorification of the printed word, which found the greatest favor in his eyes. No mere dilettantism taking its ease among its treasures, could have gathered the magnificent examples of the book-binder's art, that have been handed down to posterity with the stamp of Grolier upon them.

He gave to the book, in its most sumptuous form, a lofty and lasting position in the world of letters. To posterity, Grolier represents the spirit of the renaissance, in all its proud, splendid materialism. His personality stands out in bold relief among the many significant figures of sixteenth century France and Italy, presenting a long, busy and useful life; the life of a cultivated gentleman, the influence of which is still felt after the lapse of three centuries and has reached the new world.

C. A.

(1) The traditional date of 1476 is now known to be incorrect; for resolution of the long-standing scholarly debate on Jean Grolier's date of birth, cf. Anthony Hobson, Renaissance Book Collecting: Jean Grolier and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, Their Books and Bindings (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 6.

(2) The Astor Library is now part of the New York Public Library. The Grolier Club, which takes Jean Grolier as its patron, has a number of Grolier bindings in its collection, as well as other objects connected with the great bibliophile.